‘To Leave Things Better’

Posted on July 2, 2021

This story was printed in the latest edition of South magazine. For more stories, visit the Office of Alumni Relations.

Dr. Steve Furr remembers sitting in a room at the Battle House Hotel in downtown Mobile, preparing to interview one of the final candidates for president of the University of South Alabama.

The field was strong, but Furr couldn’t stop thinking about the person who wasn’t there. The one who had been an athlete, researcher and provost. The one who had a background in physiology and briefly led a medical school. The one who, on paper, seemed to be a perfect fit for a university about to make a big move in selecting only the third president in its 50-year history.

A candidate who was a candidate no longer, having withdrawn from the University’s search and two others. Dr. Tony Waldrop was on Furr’s mind, so he picked up the phone.

“I was trying to get him back in the search to see if he’d be interested,” said Furr, a member of the Board of Trustees who helped lead the 2014 search. “Through the whole time, once I had seen his CV I was comparing everybody to him. All the others were great, but they all had that one missing piece. They just didn’t have the diversity of experience.”

As a young athlete at the University of North Carolina, Tony Waldrop was known for his kick – the way he would, near the end of the race, turn on superhuman speed to win. He also was highly focused and self-effacing. The runner who helped lift UNC over rival Duke University for an Atlantic Coast Conference championship while battling amoebic dysentery is the same man who once told a teammate, “I am sure I will come in last. That way if I don’t, I will be more pleased with myself.”

More than 40 years later, Dr. Tony Waldrop again was about to come from behind, and he was running in an all-star meet — two of the other three finalists would go on to lead universities. Waldrop interviewed in Mobile. His credentials, administrative experience and humility were convincing. His wife was, too.

“On the plane flying back,” Waldrop recalled, “Julee said, ‘I like these people. Let’s move there.’”

Five Priorities

Today, the University of South Alabama is once again searching for a new leader, as Waldrop’s retirement date of July 1 draws near. It does so from an enviable position.

During Waldrop’s presidency, the University enrolled its most academically talented classes, significantly increased retention and graduation rates, bolstered study abroad programs, added more than a dozen degrees to its offerings and founded an Honors College. In 2020, for the first time, South surpassed $100 million in research awards.

New and renovated facilities sprung up all over the main campus. Recent construction includes the Camellia Hall student residence hall, the Health Simulation Building serving healthcare professions and the MacQueen Alumni Center. The University capped off a comprehensive campaign that raised more than $160 million. Community engagement was encouraged and supported.

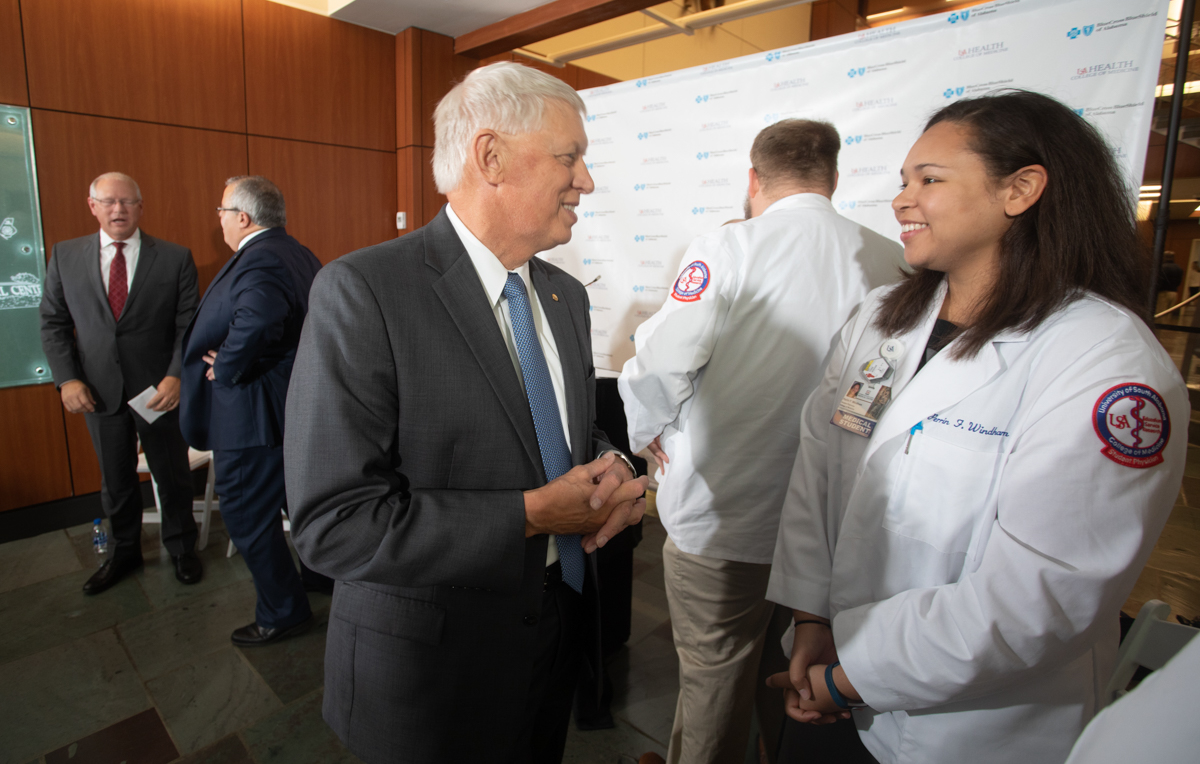

Dr. Tony Waldrop takes part in a 2019 announcement about a new College of Medicine

scholarship program funded by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama.

Dr. Tony Waldrop takes part in a 2019 announcement about a new College of Medicine

scholarship program funded by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama.

In healthcare, USA Health is thriving with an expanding footprint and additional options for primary and specialty care. The new Fanny Meisler Trauma Center went up at University Hospital; a critically-needed expanded emergency center is in the works for Children’s & Women’s Hospital; and on the fast-growing Eastern Shore, where the University’s healthcare presence was non-existent, there is a Mitchell Cancer Institute clinic, physicians’ offices and plans for the Mapp Family Campus.

The guide for this transformative growth was unveiled during Waldrop’s inauguration, just six months after he became president. It was then that he announced his five strategic priorities for South: student access and success, enhancement of research and graduate education, excellence in healthcare, University-community engagement, and global engagement.

“That was a pivotal moment in our history,” said Dr. Julie Estis, associate professor of speech-language pathology, who led the procession into the inauguration as president of the Faculty Senate. “There was a lot of excitement and newness around that whole experience of inaugurating a new president. He laid out those five priority areas that really shaped his tenure here at South.

“We can look back and see how each area has grown. There were clear priorities.”

No one could fully prepare for the biggest disruption during Waldrop’s seven-year presidency: COVID-19. The pandemic quickly forced the University and USA Health to change how they operated. Everything, including the institutions’ financial stability, was called into question.

This, of course, was happening at universities and other institutions around the world. At South, Waldrop assembled a committee that included USA Health epidemiologists and infectious disease specialists to determine a path forward. Eventually, Estis was named by Waldrop to lead the group as COVID-19 response coordinator. It is then she got a front row seat to his thought process.

“He looks at the situation through the lens of a researcher,” Estis said. “He finds out all the information about whatever topic or decision it is, and he will take time to consider it, carefully weigh it, and let that inform his decision making. He thinks through every element of a decision.”

Reaching Full Capacity

Probably the most recognizable image of Waldrop’s presidency, especially to those outside the University community, is Hancock Whitney Stadium. Construction was the subject of rampant speculation before Waldrop even arrived in Mobile, and it only grew.

At a downtown Mobile pep rally in 2015, then-Student Government President Ravi Rajendra teased the crowd with the possibility of an on-campus stadium. Attendees screamed with excitement. “Dr. Waldrop, I think that was pretty clear, so get to work,” Rajendra said from the stage.

That work began just a few years later and finished in 2020. The completion of the stadium was significant for the football program, to be sure – a recruiting tool and a long-term commitment to the Jags. For the University community, it was so much bigger – an enhancement of student life and another reason for alumni to come back to campus. The construction of Hancock Whitney Stadium was arguably the apex of a decades-long transition from USA as a commuter school to South as a regional, comprehensive and residential university.

The stadium is symbolic of other initiatives during Waldrop’s tenure. The facility was ready for the 2020 season, but with the pandemic limiting attendance, it has yet to reach full capacity. To appreciate the legacy of Waldrop’s presidency is to understand that the full success of it has not yet been realized.

In many ways, Waldrop has laid the infrastructure for a stronger University. Including literally – more than $20 million of overdue utility repairs and upgrades were made during his tenure.

Dr. Tony Waldrop, dressed from a scene in a fictional "Undercover President" episode,

greets students at Convocation, part of the annual Week of Welcome.

Dr. Tony Waldrop, dressed from a scene in a fictional "Undercover President" episode,

greets students at Convocation, part of the annual Week of Welcome.

Take, for instance, the Pathway USA program, which allows students from regional community colleges to automatically gain admission to South after completing their associate’s degree. There are now six participating institutions, and more than 1,700 students have enrolled in the program. Still, Pathway USA remains in its infancy with room for growth.

Dr. Reggie Sykes, president of Bishop State Community College, said he’s been asked at national conferences how he’s able to look past the idea that the local university might be trying to recruit students away from Bishop.

“I said it starts at the top,” said Sykes, who’s served with Waldrop on several community boards. “I have a good working relationship with the president of the University of South Alabama. We understand that we’re in this together.”

Visibly, the addition of diversity and inclusion officers at USA Health and at the University are now playing integral roles as the USA community takes part in a national reckoning on race and systemic injustice. That discussion has sometimes proved uncomfortable. At a recent Board of Trustees meeting, Waldrop walked outside to face students frustrated with the University’s handling of an issue in one of its colleges.

Rajendra said that uncomfortableness is part of a process he learned to appreciate.

“What Dr. Waldrop helped me realize is that sometimes there are situations that make you feel uncomfortable by interacting with someone who’s different from you, and you can learn from them and they can learn from you, and that’s when you’re actually able to impact a community,” said Rajendra. “So that’s the biggest lesson he really taught me. Being uncomfortable, that’s where change is actually made.”

A Collective Effort

For Margaret Sullivan, the University’s vice president for development and alumni relations, Waldrop was a leader willing to tackle tough issues but with a realistic vision of what to expect.

Compromise and contrast follow Waldrop. He’s a first-generation college student who became a University president; a healthy eater who abstains from red meat and orders fruit cups for dessert yet binges on caffeine-free, diet Mountain Dew; a CEO responsible for a $1 billion budget for whom taking credit for anything was like kryptonite to Superman. Asked for this story about his accomplishments, Waldrop swiftly interjected: “That we collectively did. You know I’m always going to say that.”

Waldrop walks quickly and reads fast, but he is also thoughtful in his deliberations. He is a president comfortable in his own skin, yet public speaking is not his strength. It is in one-on-one and more intimate settings – with everyone from students to donors – where Waldrop finds his sweet spot, Sullivan said.

“He’s very authentic, and people get when somebody’s authentic versus when they’re just superficial fluff,” she said. “It’s real with him, and I think that resonates.”

Running for Fun

Tony Gerald Waldrop grew up in Columbus, North Carolina, south of Asheville in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. His father was an industrial machinery mechanic with a sixth-grade education, his mother a high school graduate and receptionist. He was a star track athlete who attended the University of North Carolina on a full academic Morehead Scholarship.

His speed brought national notice. He was a six-time All-American, a gold medal winner in the 1975 Pan American Games and the world-record-setter in the indoor mile (3:55). Then, as the 1976 Olympics approached, Waldrop knew what he had to do.

“He had a decision to make,” recalled teammate and longtime friend Larry Widgeon. “Do I become a scientist and pursue academic exploits, or do I train for the Olympics?”

“So, he just said, ‘I’m not going to run competitively anymore. I’m going to run for fun.’”

And that was it. He got involved in coaching, earned his Ph.D. in physiology and married Julee Briscoe. The two moved around the country for his work: University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, University of Illinois, back to Chapel Hill and then University of Central Florida before landing in Mobile.

Now the couple is returning to North Carolina as Dr. Julee Waldrop takes a job as an assistant dean of the top-ranked Duke University School of Nursing. This time, he follows her.

Long before coming to South, Waldrop gave up running, even for fun. Instead, the couple walks almost every morning after waking up at 3:30. Julee Waldrop recognizes the internal drive that always has fueled her husband.

“You like to have a challenge, and when you decide on what that challenge is, you are focused on that,” she said. “And that’s been your entire life, whether that was running, or getting tenure and grants as a professor, to administration.”

“The goal,” he said, “has always been no matter what the position I had in administration is, hopefully to leave things better than the way they were. I really do think the University is better than what it was when we came here, and that gives me satisfaction.”

Drs. Tony and Julee Waldrop help students move in to residence halls in 2018.

Drs. Tony and Julee Waldrop help students move in to residence halls in 2018.