South Researcher to Lead Study on Tiny Algae Causing Big Problems

Posted on October 20, 2017

A University of South Alabama marine scientist will lead a $5 million, multi-year investigation funded by the National Science Foundation into how, when, and why certain marine toxins are produced and transferred to coral reef fish that can then threaten seafood safety.

Dr. Alison Robertson, an assistant professor in the marine sciences department, will collaborate with an international team of educators and scientists from across the United States, Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Cuba, Norway and the United Kingdom on the NSF’s Partnerships for International Research and Education (PIRE) study titled “Advancing Global Strategies and Understanding on the Origin of Ciguatera Fish Poisoning in Tropical Oceans.”

“We have assembled an incredible team of scientists from around the United States and the globe to work together on this project, so we are all excited about the opportunity and the synergistic research that we will pursue,” said Robertson, who is internationally recognized in the study of marine toxins and is a senior marine scientist at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab. “Each investigator brings unique expertise so we are able to study this important public health issue in a manner that has never been possible before.”

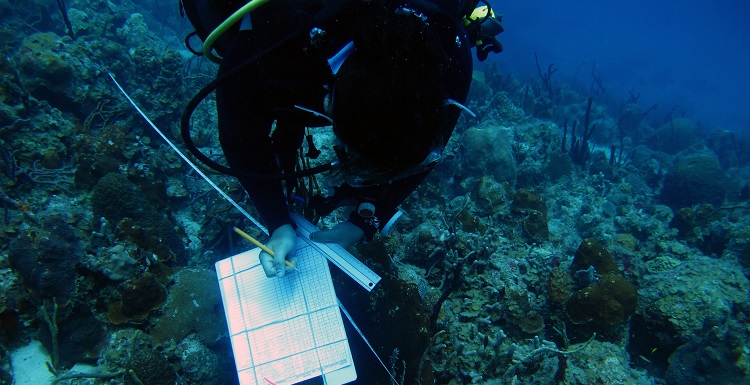

Ciguatera toxins can cause significant illness in people that consume contaminated reef fish such as barracuda, groupers, snappers, and jacks. The toxins are produced by microscopic algae that live on seagrasses and corals and enter the food web via accumulation in plant-eating fish. These small herbivores (and the toxins they contain) are subsequently eaten by top predatory fish which may be caught by recreational or commercial fishermen for food.

Ciguatera fish poisoning is estimated to affect more than 10 percent of coastal populations in tropical regions worldwide, making it the most prevalent non-bacterial seafood illness. There are currently no diagnostic tests or effective treatments for ciguatera, but small doses from a contaminated fish can cause the rapid onset of symptoms including gastrointestinal distress, neurological dysfunction, and cardiovascular abnormalities that can last up to six weeks in severe cases.

The grant will also enable investigators to engage students at multiple levels including the development of field and laboratory experiences for teachers, and students from middle school to undergraduate and graduate programs.

“We hope to foster unique and lasting education experiences for students that will develop the next generation of scientists in the marine environmental sciences,” Robertson said.