Taking On One of Life's Interrupters: Dysphagia

Posted on December 9, 2019

Swallowing. We take it for granted. We eat and drink all day long without giving it a thought.

Until there’s a problem. Each year, one in 25 adults will experience dysphagia — difficulty in swallowing. It can be a surprisingly complex problem. At the University of South Alabama, an emerging leader in dysphagia research is investigating treatments for the disorder.

“We actually stop breathing when we swallow,” said Dr. Kendrea Garand, an assistant professor of speech pathology in the Pat Capps Covey College of Allied Health Professions. “We have to time how we’re breathing in and out when we swallow. Nobody teaches us that. We’re just born with it.”

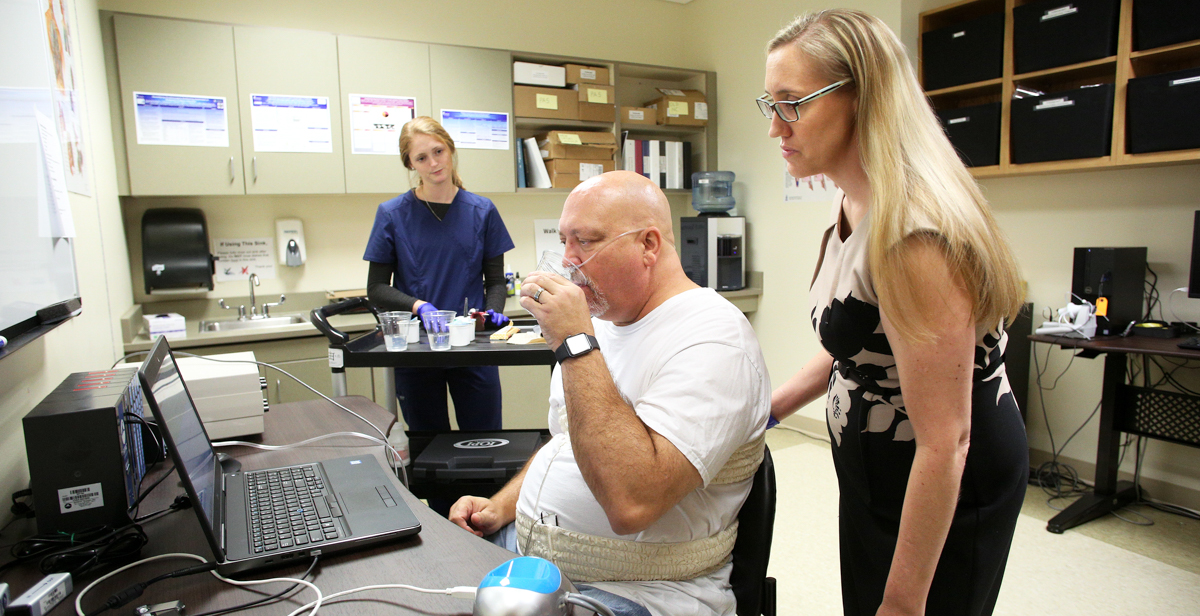

Garand founded the Swallowing Disorders Initiative Lab when she came to South in 2017. It researches how aging impacts swallowing function and especially how motor neuron disease affects swallowing. “We have an active study right now examining respiratory-swallow coordination in motor neuron disease,” Garand said.

Her interest grew out of more than a decade working as a speech-language pathologist. She saw how dysphagia could steal some of the most cherished parts of people’s lives.

“Every single thing that we do in society usually involves food and drink,” Garand said. “When we’re celebrating a birthday, we have birthday cake. You got a job promotion? Let’s go to happy hour. Everything revolves around food. And that’s not just our society. That’s societies around the world. You start taking that away ...”

She doesn’t have to finish the thought to explain how swallowing disorders can sideline someone at life’s most precious occasions. When the cause is a progressive motor neuron disease, the toll can become much crueler.

“You start taking away telling your wife that you love her,” said Garand, her voice thickening with emotion. “You start taking away asking your grandchild how her practice went. That’s hard.”

Motor neuron diseases can impact speech as well as swallowing, and many other body functions. Motor neurons are nerve cells that control voluntary muscle activity. Disease can interfere with their transmission of signals to the muscles. Muscles become difficult or impossible to control. Gradually, they weaken from disuse.

Thankfully, motor neuron diseases are rare. The most common and most famous, ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), strikes about 5,000 Americans each year. Many people know it as Lou Gehrig’s disease, after the New York Yankees baseball star who died from it in 1941. Other famous victims include the late British physicist Stephen Hawking and former New Orleans Saints football player Steve Gleason.

A mutated gene causes about 10 percent of ALS cases. What triggers the other 90 percent remains a mystery. Military veterans are twice as likely as nonveterans to develop the disease, but no one knows why.

ALS is Garand’s main research interest. She focuses on trying to improve the quality of life for those who suffer from it. For years, therapy regimens focused on conserving what strength patients had.

“We were told, ‘Don’t touch them,’” Garand said. “’Don’t do anything. Don’t fatigue them. We’ve got to save their energy.’”

New research, she said, hints that a bit of exercise might work better — that it might be possible to strengthen those wasting-away muscles and restore or at least maintain function more effectively than had been thought. “So that’s what I’m interested in. What interventions would be appropriate if these patients are shown to have this kind of discoordination between respiration and swallowing? If I do have an intervention, does that require a strengthening component?”

In the world of those who study ALS and other motor neuron diseases, Garand and her SDI lab have put South on the map. “It’s a great time to be in the ALS research world,” she said, “because there are a lot of unknowns, which is exciting as a researcher.

“But it’s also an exciting time because we can all come together. There’s this huge research organization called NEALS. That’s the Northeast ALS Consortium. Its members are all over the world. Every October we come together, and we talk about the latest research and future research. It’s great to be a part of that.”

She co-chairs a NEALS subcommittee on swallowing, which is developing clinical practice guidelines.

The three major parts of her job — research, seeing patients at the USA Speech and Hearing Center, and teaching — fit together tightly. “What I see in the clinic drives my research questions,” Garand said. “And then what I find out in the research laboratory becomes part of the clinical process.”

Her work could potentially help everyone with swallowing problems, not just those with motor neuron diseases. Older people are especially vulnerable to dysphagia. The disorder may touch as many as 22 percent of those over 50 years old.

“As you grow older,” she said, “just the age input itself doesn’t mean that you necessarily have a true swallowing disorder. But it does change how you swallow. How we try to think about it is that your reserve gets a little less.

“So a 30-year-old who has a stroke will likely have better outcomes as regard to regaining function than, say, an 80-year-old that had the same size stroke in the same location. That 30-year-old has a little more reserve.”

As she’s studying motor neuron disease patients, she’s also studying people from the general population. “I can match my ALS patient with somebody the same age and sex so we can get a better understanding of what are normal aging changes versus what truly may be caused by the actual disease itself,” she said.

All the while, Garand is working to disseminate the latest information and techniques so they can benefit patients. In 2020, USA and the University of Alabama are hosting a dysphagia conference that will take place over two days at South in June and will then repeat in Tuscaloosa in October. “I’m so passionate about the education piece of my job because we have a responsibility to train our students to improve patient outcomes,” she said.

“We have colleges of medicine and nursing on campus” she said. “We have a huge allied health college. So I’m able to work with really amazing people.”