Jewett's Mill and Labor Organizing in Reconstruction-Era Mobile

Posted on August 29, 2024 by Liam Hodges

During excavations at the Madison Street Site, we uncovered many intriguing brick features under the surface, including the remains of a cistern and structural foundations. These findings, along with research into historical documents, helped us pinpoint the Madison Street Site as the location of a strike at Jewett’s Mill in 1867, a notable episode in Mobile’s long history of civil rights action.

Brick structural remains excavated at the Madison Street Site in 2021-2022.

The incident at Jewett’s Mill occurred during a time of turmoil in Mobile. While the city survived the Civil War physically unscathed, the effects of the wartime economy and the emancipation of enslaved peoples upended the city’s economy. After the war, thousands of newly freed men and women migrated to Mobile from Alabama’s interior looking for work. In 1860, the census recorded just 102 free persons of color and 343 enslaved persons in Mobile’s Fifth Ward, which includes the Madison Street Site. By 1870, there were 1,035 people of color in the Fifth Ward, or almost 38% of the ward’s population. This meant more competition for jobs between white laborers and freedmen. Additionally, President Andrew Johnson’s lenient reconstruction plans left authority in the hands of ex-Confederates in local governments who opposed equal rights for freedmen. Between 1865 and 1867, Mobile mayor and former Confederate general Jones M. Withers passed ordinances forcing freedmen to work and restricting nonwhite workers to low-paying jobs. These factors led to a tense situation that boiled over in the spring of 1867.

According to newspapers from the time, unrest among Black workers at the mills and riverfront docks began in mid-March 1867 and came to a head on Saturday, March 30. On that day, Black dockworkers went on strike to demand a pay raise from $.25 per day to $.50. One of the leaders from that demonstration was arrested after strikers blocked white replacement workers from entering the docks. On the same day, the Mobile Advertiser-Register reported a work stoppage by Black workers at a sawmill “in the lower part of this city” owned by John F. Jewett. The leader of the strike was a Black sawyer and ex-employee of Jewett named Wylie Brown, who encouraged other workers to strike for a raise from $1 to $1.5 per day. Jewett himself soon arrived on the premises.

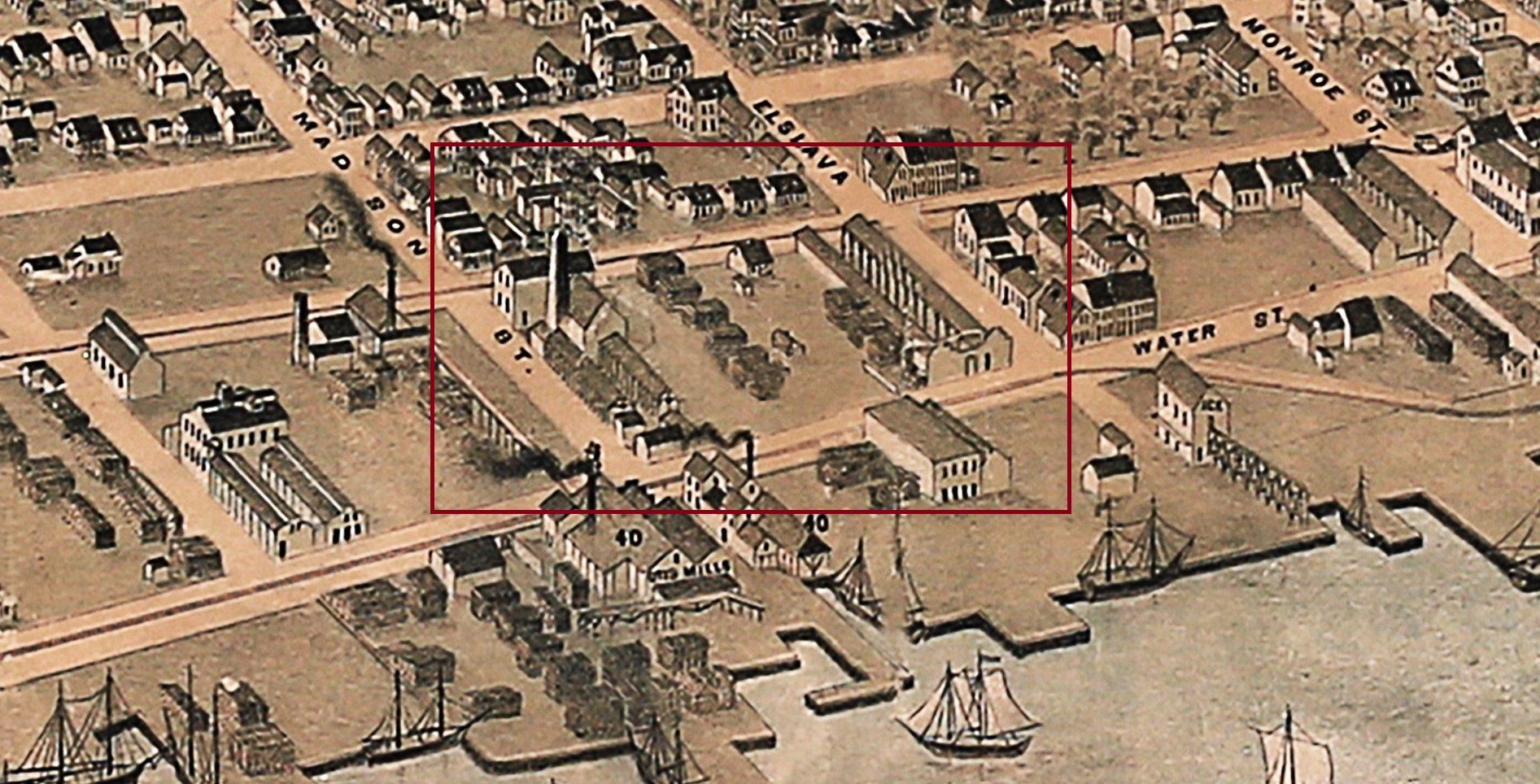

1873 Augustus Koch Map showing the Madison Street Site. This 1873 bird’s-eye-view map of Mobile depicts Jewett’s Mill in the upper left corner of the red box.

There are conflicting accounts of what happened next. The Advertiser-Register and the Mobile Daily Times, two papers which were not sympathetic to the plight of Black workers, reported that Brown had trespassed against Jewett and was arrested and brought to the city jail. The Mobile Nationalist, a pro-reconstruction paper published by Lawrence Berry, stated that Jewett physically attacked Brown and had him “hauled through the public streets like a hog.” All sources, however, agree that his arrest drew a large and “excited” crowd of Black and white observers to the jail. Two days later, Brown was tried in front of a packed courtroom. Alderman Overall, acting mayor of Mobile, dismissed the charges of disorderly conduct against Brown due to a lack of evidence, to the relief of his supporters.

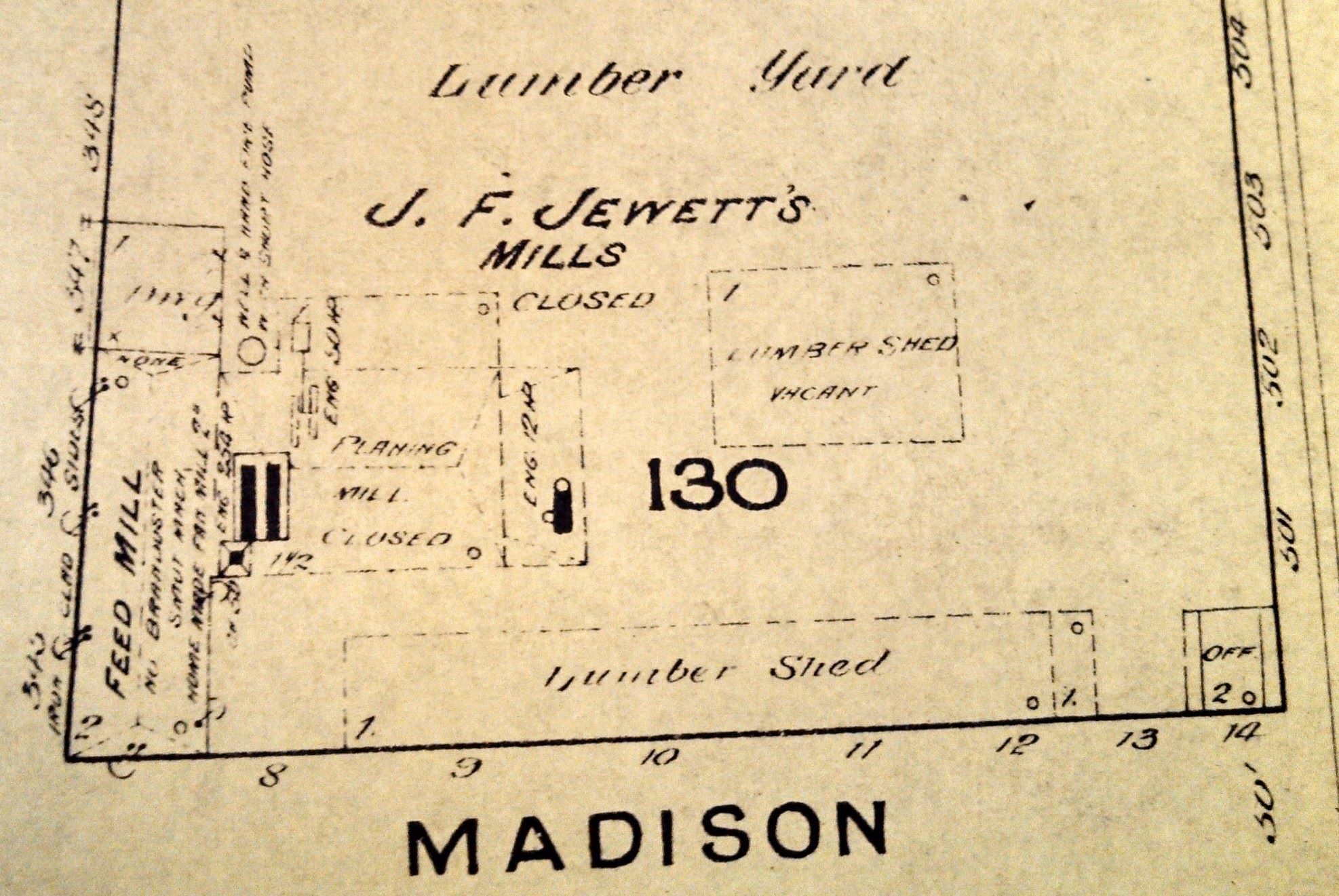

1880 Fire Insurance Sanborn Map courtesy of the Mobile Municipal Archives. Jewett’s Mill as it appears in the 1880 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map. Note the circular well near Royal Street, above the “8” on Madison.

Initially, our team suspected the strike may have occurred in our project area for the I-10 Mobile River Bridge Archaeology Project, but there was some question of the exact location of the mill. Based on deed records, we knew Jewett had purchased several nearby properties which were also used as lumberyards or mills around 1852. One clue came from the Mobile City Directory of 1861, which placed Jewett’s Mill at the northeast corner of Royal & Madison. This was corroborated by the 1880 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of Mobile, seen above, which labeled the site as Jewett’s Mill. The map even shows a well in the same location as a brick cistern we uncovered during excavations (shown below), giving us confidence we were in the right spot.

Circular brick feature excavated at the Madison Street Site in 2021-2022.

The strike at Jewett’s Mill was part of a wave of direct-action protests by Black Mobilians in early 1867. Not even two years after the end of the Civil War, these incidents remind us that organized protests by African Americans began long before the well-known civil rights movement of the 1950s. Tying the event to the structural remains we found at the Madison Street Site is just one example of how we can bring together historical sources and archaeological data to bring Mobile’s past into clearer focus.

Sources & Further Reading:

“A Negro Strike,” Mobile Daily Times, April 2, 1867.

“A Singular Case,” Mobile Advertiser-Register, April 3, 1867.

“Discontent Among the Negro Laborers,” Mobile Advertiser-Register, April 2, 1867.

Brent, Joseph Edgar. “No Surrender: Mobile, Alabama During Presidential Reconstruction, 1865-1867.” Master’s Thesis, University of South Alabama, 1988.

Fitzgerald, Michael W. Urban Emancipation: Popular Politics in Reconstruction Mobile, 1860-1890. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2002.