The Virginia Street Site and Mobile's Streetcar History

Posted on May 28, 2024 by Liam Hodges

During excavations at the Virginia Street Site in early 2022, our archaeologists uncovered this intriguing artifact: a streetcar token for the Mobile Light & Railroad Company (M.L.&R.R. Co.) from 1916, pictured here. We found the token (shown below) near the former site of a house at 906 South Franklin Street in Mobile’s Down the Bay neighborhood. This house was owned by Jesse and Lillie Owens in 1897 and remained in their family until 1962. Artifacts like this token give us a window into the daily lives of people like the Owens Family and show us the importance of public transportation for people who lived Down the Bay in the early 20th century.

A token for the Mobile Light & Railroad Company dated 1916, reading “Good for One City Fare” on the opposite side. The token we found is on the left, with a more pristine example on the right.

The first streetcar line in Mobile was the Mobile & Spring Hill Railroad, chartered by the State of Alabama in 1860. The company had one line running between Commerce Street to Spring Hill College. Over the next twenty years numerous privately-owned and independent rail lines opened, which gradually consolidated into the Mobile Street Railroad Company by 1890.

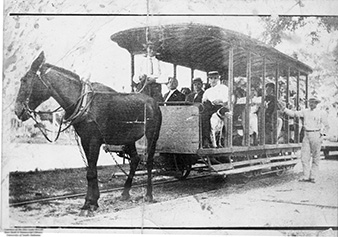

Mule-driven streetcars like this were Mobile’s earliest form of public transportation. Photo courtesy of Archives Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.

Until the 1890s, most streetcars in Mobile were drawn by mules or occasionally steam-powered “dummy” engines. In 1892, businessman James H. Wilson received a franchise to build an electrically-powered rail line from Conti to Royal to New Jersey streets and back again. These new streetcars received electricity via overhead wires from a central power house located on the corner of Monroe and Water Streets, right next to the South Royal Street Site near the current Mobile Cruise Terminal. These new electric trolleys were faster, larger, cleaner, and more reliable than the mule-driven cars. They were so successful that within 10 years, Wilson’s Electric Railroad Company absorbed the other two streetcar companies into the Mobile Light & Railroad Co., gaining a monopoly on public transit in the city.

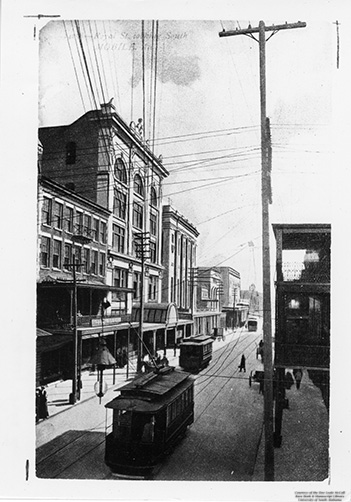

A scene of electric streetcars running along Royal Street, facing south. Photo courtesy of Archives Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.

In 1908, the Mobile Light & Railroad Company had 50 miles of track along twenty different lines, which were serviced by 117 passenger cars. A map of the lines in 1908 can be seen on the Alabama Department of Archives and History digital collections. The company had a car barn on Canal Street, where the Ryerson building is today, and immediately south of the Old Water Street Site. In addition, the company built and serviced cars at Monroe Park, situated on the Mobile Riverfront south of Choctaw Point. The M.L.&R.R. Co. built Monroe Park to double as a leisure destination for Mobile’s urbanites, with a baseball field, carousel, restaurant, and dance pavilion. The park proved popular and allowed the railroad to boost ridership on weekends and holidays.

The M.L.&R.R. Co.’s car barn and machine shop at Monroe Park, south of Choctaw Point. Photo courtesy of S. Marion Coffin Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.

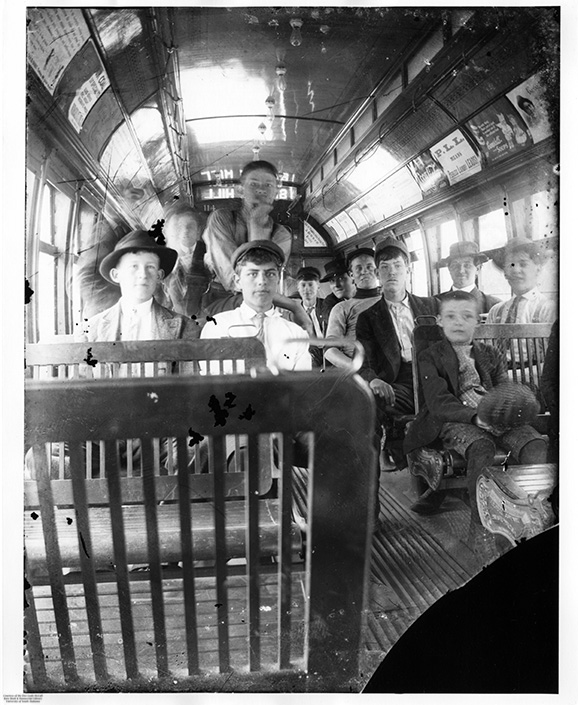

The Mobile Light & Railroad Company’s streetcars were designed by master mechanic S. Marion Coffin. Coffin also took many photographs of the railway’s operations featured in this post. Most cars could carry twenty to thirty people at speeds up to thirty miles-per-hour. Some larger cars like those that ran to Pritchard carried fifty people. Open-sided cars were also popular in the hot summer months. Originally, each car had a conductor who collected passenger’s money when they requested him to stop the trolley. Starting in 1913 conductors were replaced with pay-as-you-enter coin boxes, where riders deposited tokens like the one found near the Owens home.

Passengers inside a streetcar. Photo courtesy of History Museum of Mobile Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.

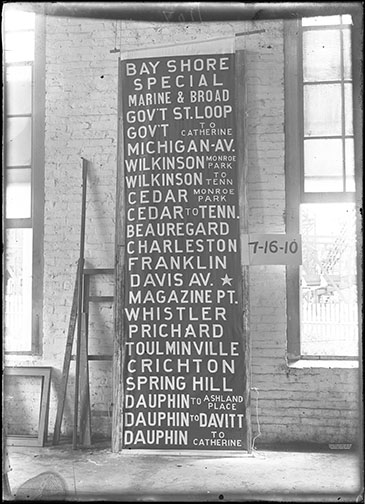

Many of the streetcar lines carried riders between downtown Mobile and the suburbs. Down the Bay was covered by several lines, including the Franklin St. Line which passed directly in front of the Owens home. Jesse Owens possibly rode this line north to the Louisville & Nashville Railroad yards where he worked as a laborer and fireman for over thirty years. Streetcars provided a fast and reliable transportation service for students and workers living outside city centers, allowing them to live further away from where they went to school or worked, promoting the growth of suburbs in cities across America.

A board showing Mobile’s streetcar routes. Photo courtesy of S. Marion Coffin Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.

Despite this greater accessibility of travel, access to streetcars in Mobile was not equal. While Mobile had no legal segregation on public transit before 1902, and white and black passengers shared cars, social custom and intimidation promoted separated seating by race. Streetcars were especially important for black workers like Jesse Owens who worked in Mobile’s vital industries in the dockyards, railroads, or as domestic servants. In October 1902, the city council passed an ordinance allowing streetcar drivers to assign black riders to sit in the back of the cars. Black Mobilians, encouraged by local black clergymen, boycotted the streetcars and opted to walk instead. Although we don’t know for sure, it is possible that the Owens family partook in the boycott for a time.

By the second month of the boycott, the M.L.&R.R. Co. started to feel the boycott’s economic impact, and company President James H. Wilson ordered his employees not to enforce the new ordinance. The boycott eventually collapsed, and the segregation ordinance remained in place until the 1950s. Mable Dennison, a resident of Down the Bay, recalled the significance of segregation on streetcars and buses in an oral history interview from 1999:

“Well on the buses, it was the same as the streetcars, had been the same procedure, where the white people would sit in the front and the black people would sit near rear… And it wasn’t until white people actually moved out of the area, or white people had better transportation, that things got better for traveling for black people, cause black people as a rule didn’t have cars, didn’t have their personal transportation, and many of them had to ride the buses.”

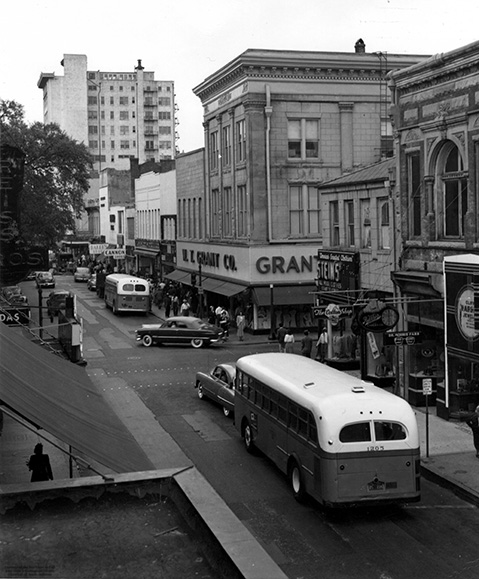

In the 1940s, Mobile City Line’s buses replaced streetcars as Mobile’s main form of

public transit. Photo courtesy of Erik Overbey Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare

Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.

In the 1940s, Mobile City Line’s buses replaced streetcars as Mobile’s main form of

public transit. Photo courtesy of Erik Overbey Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare

Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.

The rise of personal automobiles, taxis, and buses spelled the end for Mobile’s streetcars. James H. Wilson died in 1939, and the Mobile Light & Railroad Company was taken over by National City Lines, who renamed the company to Mobile City Lines. The company gradually started introducing bus services in 1939, and the last streetcar completed its final route on March 10, 1940. With the backing of interests from the automotive and oil industries, policymakers at the local and federal levels in the mid-20th century prioritized building car-based infrastructure like freeways over public transportation. Despite some interest in reviving light rail in the 1980s and 1990s, buses are still Mobile’s only form of public transportation.

The token we found is just one example how one artifact can lead us down different avenues of historical research. Follow our blog as we continue to share more of our insight into the history of Down the Bay and Mobile through our work for the I-10 Mobile River Bridge Project.

Sources and Further Reading:

- Alsobrook, Daniel E. “The Mobile Streetcar Boycott of 1902: African American Protest or Capitulation?” The Alabama Review (April 2003), 83-103.

- Beverly, Frances. “Street Railways,” Frances Beverly Papers, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL

- Dennison, Mable. Interview by Kern Jackson at Mable Dennison’s home, 811 St. Emanuel St., Mobile, Alabama, on July 15, 1999. On file at the Mobile Public Library

- Rose, Mark H. and Mohl, Raymond A. Interstate: Highway Politics and Policy Since 1939, 3rd Ed. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2012.

- Sparks, Asa H. “Mobile Trolleys,” Traction & Models (July 1967), 11-14.

Newspaper Articles:

- “57-Year History of Car Lines in Mobile Is Told,” Mobile Register, Unknown Date, 1925.

- “Death Claims Business Man,” Mobile Daily Times, August 2, 1939.

- “Ceremony Absent as City Sees Last of Electric Cars,” Mobile Register, March 10, 1940.

- Lee, Ed. “Last Trolley Bell Sounded Knell for Colorful Era 20 Years Ago,” Mobile Press Register, March 6, 1960

- Connell, Moody. “Trolley Motormen Expected the Unexpected,” Mobile Register. December 17, 1961.

- Daugherty, Frank. “Can Mobile Support Light Rail Transit?”, Mobile Register, October 26, 1982.